This was written as one of the poems at the memorable Illuminate Rotherhithe festival in 2023 Poem -In praise of Rotherhithe . . Rotherhithe, Rotherhithe let us now praise The…

Screenshot[/caption] Lines written after visiting “Monet in London” When Monet sought a painting revolution He saw smog filled London as a solution After one look at the evening sky Pollution…

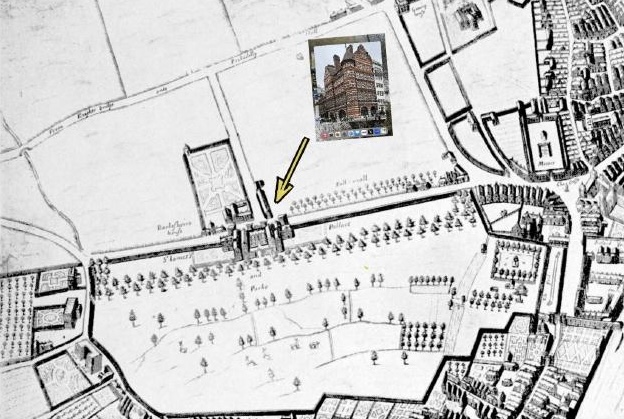

The building with an arrow pointing to it on this 1658 map at the corner of Pall Mall and St James’s Street was a royal tennis court built by Henry…

It was down to the holiness of St Columba To wake Scotland from a time-warped slumber He not only gave God to the people Complete with bell, book and steeple…

I walk by the Thames I know so well Caught again by a riverine spell I know you well but I know you not An endless flow without a plot…

Who ever knew Truth be put to flight By falsehood in an open fight? So said Milton and if truth be told It was widely swallowed in his day That…

London is curiously at ease Invaded twice daily from overseas But the Thames knows Where it goes Its tide with the moon communes Mornings and afternoons Changing its course Each…

I have been deeply moved by the reaction to my book and as a lot of readers have bought multiple copies to give as presents I thought it might be…

Spring in the Park Daffodils the park adorn Winter Hawthorn is reborn Willows now are weeping green The robin looks for crumbs unseen Buds unfolding now are free Spring is…

This has been running on a computer 24/7 for over 20 years in an attempt to get an algorithm to replicate a two line poem as a small contribution to…

What happened when artificial intelligence brain ChatGPT challenged my poem with two of its own

This is Poem I wrote when I was starting to suffer from writer’s block during the Covid lockdown UNTIL it hit me it was just a joke Something that happened…

What3Words.com locates any space of 3m square using only three words. As lockdown therapy I hesitantly tried a poem which contains a 3 word location (in the right order!) so…

Poem: The Thames at source I went to a shrine without compare To see a river that wasn’t there We strolled from the station forecourt at Kemble Where walkers, like…

The Thames Flow London is curiously at ease, Invaded twice daily from overseas But the Thames knows Where it goes Its tide with the moon communes Mornings and afternoons Changing…

Scene 1 Puck If we shadows have offended . . . Give me your hands, if we be friends, And Robin shall restore amends. Stage blacks out and the lights…