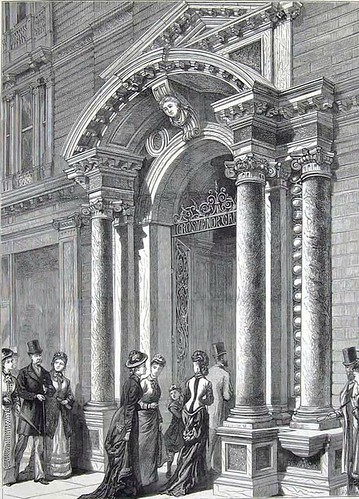

Belstaff boutique (left) with Doric columns dating from 1925 and (right) as it looked in 1877

It is easy to walk past 135/137 New Bond Street – currently a flagship fashion shop for Belstaff – without having any inkling that it helped to launch two disparate revolutions in the nineteenth century when it was known as the Grosvenor Gallery.

In Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, Lord Henry says that the painting of Dorian is so good it should be sent to the Grosvenor Gallery because the Royal Academy is too large and vulgar: “Whenever I have gone there, there have been either so many people that I have not been able to see the pictures which was dreadful, or so many pictures that I have not been able to see the people which was worse. The Grosvenor is really the only place.”

So it was in those days, a custom-built gallery where modern paintings could be hung that had little chance of being accepted by the ultra conservative Royal Academy nearby. For the opening ceremony in 1877 Oscar came in a suit shaped like a cello.

It was at the Grosvenor that John Ruskin, famously said that Whistler’s painting Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket was “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face”. Whistler sued, won, and after being given a measly farthing in damages was plunged into bankruptcy. The original entrance (right) is reputed to come from Palladio’s Church of St Lucia in Venice when it was demolished to build a railway station.

But the Grosvenor Gallery’s lasting claim to fame is that it was the birthplace of the modern electricity grid. Sir Coutts Lindsay, who built the gallery – helped financially by his wife, a Rothschild ,- achieved fame and fashion by creating a temple to contemporary art but never made any money out of it until 1883 when he decided to use recently invented electricity generators to light the gallery. It proved so successful that neighbours wanted to be supplied from his generators and, with the help of Sebastian Ferranti – these days acknowledged as the father of the National Grid – he eventually supplied electricity from Regent’s Park to the Thames and from Kensington to the City of London.Although the building has had other uses since, including as a concert hall by the BBC and on one occasion the Beatles, it is as the unusual cradle of modernity in both the arts and electricity for which it will long be remembered. But not yet so remembered as to merit a blue plaque.

To receive updates 2 or 3 times a month write your email address in the box on the right. You can follow me on Twitter @vickeegan